This was originally posted on my personal blog, the Gecko’s Bark in 2007; it was later posted on Barking Book Reviews in 2011.

Julie Phillips Brings James Tiptree, Jr. Back to Life

Her in-depth biography of the ground-breaking science fiction author illuminates the life of a literary recluse

Writing a nonfiction book and making it both interesting and entertaining is not always easy to do. Writing an in-depth biography on a relatively obscure author and making it interesting and entertaining to read over the course of the entire book, all while squeezing in historical lessons on the feminist movement and gender roles, is certainly even more challenging.

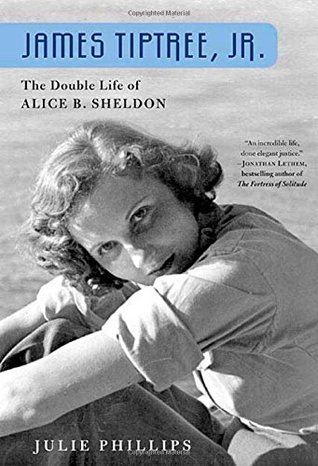

But author Julie Phillips proves adept at doing just this with her biography on science fiction author Alice B. Sheldon. James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon is an exhaustive look at Tiptree’s life, illustrating that she is one of the more fascinating characters in the pantheon of oddballs known as science fiction authors (and I say oddballs as term of love and endearment). By all rights, this book should be the literary equivalent of watching paint dry: a book about someone who writes written by a journalist by profession.

But in fact Phillips’ book proves hard to put down. While this is largely because of her subject matter, it is also in no small part because of her writing. Throughout her linear portrayal of Sheldon’s life story (another reason this book should be boring), Phillips sprinkles her text with context and insight, both her own and that of Sheldon’s contemporaries, those who knew her as the colorful figure she was in life, and those that knew her only through her correspondence as a reclusive science fiction writer James Tiptree, Jr., her nom de plume.

But at no point does the book ever get bogged down in either biographical or contextual detail. Again, that is partly because of the interesting subject matter; Sheldon had a colorful outer life by anyone’s standards, as well as a dark and troubled inner life. As others have noted, including one of my favorite contemporary science fiction authors, William Gibson, this is an exhaustive and entertaining biography that Sheldon surely deserves.

Even if one is not interested in science fiction and has never heard of Sheldon/Tiptree, Phillips’ book may still prove a fascinating read, as it details the life of a woman from the Greatest Generation. Sheldon actually enlisted – to the extent that women could – in the U.S. military in WW II, and later worked in intelligence, specializing in photographic interpretation, and later worked briefly for what became the CIA.

As such, Sheldon was a first-hand witness to the social changes that occurred in women’s roles in our culture, from the first tentative steps of the feminist movement before and during WW II to the social upheavals that occurred in the 1960s and 1970s. Sheldon’s life, and one could say her psyche, straddled this pivotal point in modern history, and her writing reflected this. In fact, many of the feminist science fiction authors that were Sheldon’s contemporaries – science fiction was a bastion of feminist fiction at the time, and a front for gender battles, as Phillips details – hailed Tiptree as a man who “got” feminism and women. Phillips’s subsequent exploration into why Sheldon felt more comfortable writing with a male persona in Tiptree is fascinating, to say the least, and provides an insight into that time in American culture that I doubt most history texts provide.

Even Nerds Can Be Sexist Swine

It’s really hard to understand bigotry in general and sexism in particular. One reason for this is, I suppose, the fact that I’m a guy, and as such, I’m not routinely subject to sexism. But then my father has told me that he made it a point to raise my siblings and I to be as open minded as possible (I should note that he and my mother are both from the same generation as Tiptree, albeit slightly younger, but my father also served in WW II). That same father suffered a heart attack when I was 10 and took early retirement; my mother went to work and dad became the house husband, taking over the bulk of the domestic chores (he once even turned all my adolescent tidy whities pink). This experience has no doubt something to do with my outlook.

In any event, as a sci-fi nerd from an early age, I read all the classics as a kid – Clarke, Asimov, and so forth, and later, in high school, getting into Heinlein — adolescent boys probably shouldn’t read Heinlein, come to think of it — and some of the harder sci-fi. Then there was space opera type stuff – my fellow Gen Xers and I were raised on Star Wars, after all. It was in college that I began to discover some of the women authors that were Tiptree’s contemporaries, such as Ursula K. Le Guin and later Joanna Russ and Marge Piercy – as well as Tiptree himself … er, herself.

I encountered some of these authors in a women studies class and in an English class that concentrated on women authors (I have to come clean here: while one reason I took these classes was genuine interest, the fact that they fit in my schedule and tended to be inhabited by all manner of interesting and attractive alternachicks factored into my decision). What I didn’t know and didn’t learn – until I read Phillips’ book, and this surprised me – was that women writing science fiction was such a hot button topic in the sci-fi community itself in the 1970s; apparently there were many (men, of course) who thought that women couldn’t write “real” or “hard” science fiction. Ironically, some of these same people also thought that Tiptree was most definitely male – Tiptree’s gender and true identity were a frequent hot topic of discussion within the sci-fi community, as Phillips portrays.

The idea that women can’t write real science fiction merely because of their biology is of course complete rubbish, as evidenced by the aforementioned authors’ work, and many others — Rebecca Ore (Rebecca B. Brown), A.C. Crispin and Ann McCaffrey come to mind right off. As for the ability of women to grasp and write hard science fiction, Sheldon herself was playing around with hard science in her writing; her stories exhibited characteristics of hard sci-fi even before the term had come into vogue.

She was certainly aware of orbital mechanics, and the problems introduced by traveling at or near the speed of light (such as the relative passage of time between a spaceship and its planet of departure – obviously she had read up on Einstein). There were no shipstones or warp engines for Sheldon’s spaceships; her space-going vehicles also depended on rotation to simulate gravity – no convenient artificial gravity on her spaceships, either. So the fact that many of the very names I had cherished in the sci fi pantheon of authors, the people (men) that were so forward looking, were saying that women couldn’t write sci-fi – that was surprising news to me.

I was aware of course that women authors in general had fought an uphill battle against sexism over the years; Sheldon was hardly the first female author to secretly publish under a male pseudonym. And I have read some militantly feminist science fiction here and there over the years. But until having read Phillips’ book, I guess I thought that science fiction would have been one genre where sexism wouldn’t have been an issue — at least not among its cognoscenti.

After all, us sci-fi nerds, we understand what it’s like to feel alienated and judged not on our own merits but on people’s preconceived notions. We should know better than to subscribe to sexism or any other sort of bigotry; that just reeks of hypocrisy. But then Alice Sheldon’s life, particularly after James Tiptree, Jr. was outed as a female author, is a mountain of evidence to the contrary.

Fortunately for us, Phillips presents that mountain of evidence in a captivating and at times brilliant package. While one can’t help but wonder what Sheldon would have written had she not killed herself in 1987 at age 71, or what she might have written had she been born later, say in the 1950s or 1960s, she nevertheless leaves behind a wonderful body of work that, like all science fiction, is not a reflection of the future but of the times in which it was written. With Julie Phillips’ James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon, she also gets a fitting epitaph, and we readers get a lesson in literature and modern history.

Incidentally …

Here is an NPR interview with Julie Phillips regarding Tiptree and her biography.

Also, in an article for the New Yorker’s Postcript on Ursala K. Le Guin, written shortly after here death in January, 2018, Phillips revealed that she is working on the Earthsea author’s biography.