Originally appeared on June 2, 2011 in Barking Book Reviews.

A U.S. Ambassador to Nazi Germany Provide’s a Unique Perspective on Hitler’s Rise to Power

Perhaps for many who look back at World War II, the one that happened after the War to End All Wars, the most obvious lingering question is how Hitler and the Nazis came to power, and how the regime was able to do the terrible things it did, namely the holocaust. Particularly when we consider that only two decades before much of the world was swept up in a war dominated by German empire and militarism. How did we — we being the Allied powers — let that happen?

Erik Larson attempts to answer this question, at least in part, with his book In the Garden of Beasts. Some might find that the book isn’t satisfying, or at least not satisfying enough, as it is limited in its scope. It inevitably touches on these large questions, but Larson doesn’t set out to rewrite William L. Shirer’s seminal work, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. So this isn’t necessarily a flaw or a problem with the book per se, but it does leave one hungry to learn more, to delve into the answer to this question more deeply. This is to the book’s credit, however. As Larson himself says at the beginning of the book:

There are no heroes here, at least not of the Schindler’s List variety, but there are glimmers of heroism and people who behave with unexpected grace. Always there is nuance, albeit sometimes of a disturbing nature. That’s the trouble with nonfiction. One has to put aside what we all know — now — to be true, and try instead to accompany my two innocents through the world as they experienced it. These were complicated people moving through a complicated time, before the monsters declared their true nature.

Even those with a casual interest in history will find In the Garden of Beasts a worthy and interesting read; students of World War II history will no doubt find it compelling reading.

Glimmers of Heroism

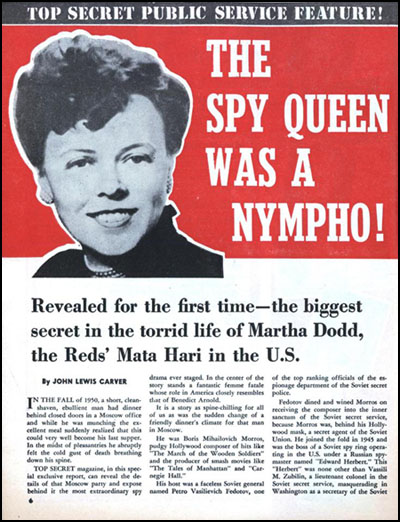

A journalist by trade before he began authoring nonfiction books, In the Garden of Beasts looks at the early years of Nazi Germany, specifically 1933 and 1934, through the eyes of American diplomat William Dodd, and his daughter, Martha – Larson’s two innocents abroad (Martha Dodd, incidentally, is worthy of a biography in her own right). True to his roots as a journalist, Larson sticks largely to first person accounts – journals and diaries, personal letters, diplomatic communiques and the like – as his source material; anyone quoted in the book is quoted from material that they actually wrote at the time.

So what Larson elaborates is a view of the Third Reich just having come to power with Adolf Hitler as chancellor; at the time Dodd arrives in Berlin, Hitler and his allies are moving to consolidate their power and authority over the country. This culminates in the infamous Night of the Long Knives – the bloody purge of the paramilitary Stormtroopers – followed shortly by the death of the German president, Paul von Hindenburg, who represented the last obstacle between Hitler and absolute control over Germany.

We see these events from the two disparate perspectives – disparate initially, although converging in the end – of Dodd, who was 63 at the time of his appointment in June of 1933, and Martha, who was 25 at the time she first arrived in Berlin. Dodd perhaps has a unique perspective on events; he certainly was an unusual choice on the part of President Roosevelt as U.S. ambassador to Nazi Germany. Dodd was a well-respected professor of history by trade, who happened to have earned a PhD at the University of Leipzig in Germany in 1900 – he spoke German and professed a fondness for the Germany of his youth. Although he was active politically – he was good friend of President Woodrow Wilson and described himself as a Jeffersonian democrat – he had never been involved with the U.S. foreign service or its diplomatic corps.

While Dodd was well-to-do by the standards of much of America in the early 1930s – the early years of the Great Depression – having a small farm in Virginia and a residence in Chicago, as well as his own automobile, he was a man of modest means compared to the good-old-boys club of the U.S. diplomatic corps. The fact that he wasn’t part of this so called “Pretty Good Club,” and approached his diplomatic post as an historian with a sober and no-nonsense attitude caused almost immediate conflict with those in the otherwise rarefied world of international diplomacy, including his colleagues in the U.S. State Department.

As Larson notes, Dodd himself suggests before he leaves for his post in Berlin “that his temperament was ill suited to ‘high diplomacy’ and playing the liar on bended knee.” But then this is what makes Dodd’s story compelling; he was much closer to Middle America than what we would perhaps describe now as a beltway insider. And it is this that brings us to what is so tragic about Hitler’s rise to power: there were people in Germany in the early 1930s that saw what was happening – the consolidation of power, the brutal repression of dissent and civil rights, the subjugation of Jews, the military buildup – and tried to warn the outside world; Dodd was among them.

But as it happened, Dodd’s major task as determined by Roosevelt and his advisers wasn’t necessarily to try and provide a moderating influence on the fascist regime. No, his job was to convince Germany to repay its debts to American business interests. The president did instruct Dodd to provide an example of American ideals while in Berlin in hopes that this might provide some positive influence, but the primary goal was to convince German business to repay that considerable sum.

But it is through Dodd – and Larson – that we begin to see how the world let Hitler happen, so to speak. In a civilized world still weary from the previous World War and in the depths of the Great Depression, it was hard for many to conceive of what was happening in Germany and where it could lead; Dodd was no different. As Larson tells us, “ever a student of history, Dodd had come to believe in the inherent rationality of men and that reason and persuasion would prevail, particularly with regard to halting Nazi persecution of Jews.” Even when confronted with damning first-hand reports, Dodd doesn’t truly grasp the German situation at first. George Messersmith, the head of the American Consulate in Germany at the time of Dodd’s appointment as ambassador, had already been sending numerous warnings back home to Washington. These communiqués were Dodd’s first real clue about what was happening to Germany under the Third Reich. Says Larson:

It was one thing to read newspaper stories about Hitler’s erratic behavior and his government’s brutality toward Jews, communists, and other opponents, for throughout America there was a widely held belief that such reports must be exaggerated, that surely no modern state could behave in such a manner. Here at the State Department, however, Dodd read dispatch after dispatch in which Messersmith described Germany’s rapid descent from democratic republic to brutal dictatorship.

I would describe myself as probably having a somewhat more avid interest in history than the average person – call me a casual history buff and would-be scholar. But even I must admit that I wasn’t aware that by 1933 there were already concentration camps, and the repression of Jews and other groups was commonplace and out in the open, as Larson establishes In the Garden of Beasts. In fact no less than Hitler himself suggests to Dodd that Jews have to be removed from Germany by one means or another. So it is all the more astonishing in retrospect that nothing was done until it was too late and German troops were sweeping across Europe.

But even after Dodd has been in Germany for some months and saw for himself the brutal repression taking place in the streets – American travelers in Germany were no safer than anyone else, and attacks on foreign travelers by brown-shirted Stormtroopers was not uncommon – his belief in a rational world won’t let him fathom that this sort of behavior could persist for very long. He felt that the Hitler regime would surely either have to moderate its stance or be removed from power; it was apparently a common belief throughout Europe and the Americas. As Larson elaborates:

Messersmith met with Dodd and asked whether the time had come for the State Department to issue a definitive warning against travel in Germany. Such a warning, both men knew, would have a devastating effect on Nazi prestige. Dodd favored restraint. From the perspective of his role as ambassador, he found these attacks more nuisance than dire emergency and in fact tried whenever possible to limit press attention. He claimed in his diary that he had managed to keep several attacks against Americans out of the newspapers altogether and had “otherwise tried to prevent unfriendly demonstrations.”

Dodd meets with Hitler himself and sees his manic personality first hand – but even Hitler’s evident hysteria isn’t quite enough, unbelievable as it is.

It was a strange moment. Here was Dodd, the humble Jeffersonian schooled to view statesmen as rational creatures, seated before the leader of one of Europe’s great nations as that leader grew nearly hysterical with fury and threatened to destroy a portion of his own population. It was extraordinary, utterly alien to his experience.

But as Larson documents, within a year Dodd realizes that Messersmith and others, namely Jews that had already escaped Germany and the foreign press corps stationed there, are right: Hitler and his ilk are madmen, madmen with a firm grip on the German nation. And that they are madmen preparing for war; any declarations of peaceful intent were simply diplomatic smoke and mirrors.

Later, Dodd wrote a description of Hitler in his diary. “He is romantic-minded and half-informed about great historical events and men in Germany.” He had a “semi-criminal” record. “He has definitely said on a number of occasions that a people survives by fighting and dies as a consequence of peaceful policies. His influence is and has been wholly belligerent.” How, then, could one reconcile this with Hitler’s many declarations of peaceful intent? As before, Dodd believed Hitler was “perfectly sincere” about wanting peace. Now, however, the ambassador had realized, as had Messersmith before him, that Hitler’s real purpose was to buy time to allow Germany to rearm. Hitler wanted peace only to prepare for war. “In the back of his mind,” Dodd wrote, “is the old German idea of dominating Europe through warfare.”

Casual Racism and Perception of the Jewish Problem

In contrast to Dodd we have his daughter, Martha. A Jazz-Age child, Martha is perhaps more representative of the outside world’s attitude toward the warnings coming out of Germany. As Larson shows us early in the book, Hitler is viewed by many as a joke, this silly little man with a goofy mustache – how can he be a threat?

For her, however, the prospect of the adventure ahead soon pushed aside her anxiety. She knew little of international politics and by her own admission did not appreciate the gravity of what was occurring in Germany. She saw Hitler as “a clown who looked like Charlie Chaplin.” Like many others in America at this time and elsewhere in the world, she could not imagine him lasting very long or being taken seriously. She was ambivalent about the Jewish situation.

She clarifies that ambivalence herself:

“I was slightly anti-Semitic in this sense: I accepted the attitude that Jews were not as physically attractive as Gentiles and were less socially desirable.” She also found herself absorbing a view that Jews, while generally brilliant, were rich and pushy. In this she reflected the attitude of a surprising proportion of other Americans, as captured in the 1930s by practitioners of the then-emerging art of public-opinion polling. One poll found that 41 percent of those contacted believed Jews had “too much power in the United States;” another found that one-fifth wanted to “drive Jews out of the United States.” (A poll taken decades in the future, in 2009, would find that the total of Americans who believed Jews had too much power had shrunk to 13 percent.)

Indeed, that’s another astonishing thing for us to discover here in 2011 – the casual racism toward the Jews. Not that it existed – that’s hardly surprising; racism must surely rank with prostitution in terms of age and human history. Rather, it’s just astonishing how open and accepting people were about it, including politicians, career politicians that would document their racist views, surely knowing that they would be published. Here in the information age when considerably smaller faux pas can ruin a political career nearly instantly, it is almost unbelievable. For example, William Phillips was U.S. under secretary of state under Roosevelt at the time of Dodd’s appointment. As Larson notes, Phillips made no effort to hide his racist beliefs:

Phillips loved visiting Atlantic City, but in another diary entry he wrote, “The place is infested with Jews. In fact, the whole beach scene on Saturday afternoon and Sunday was an extraordinary sight – very little sand to be seen, the whole beach covered by slightly clothed Jews and Jewesses.”

Apparently Jews on the beach in Atlantic City was a big issue for prejudicial folks back then. As Larson notes, Wilbur J. Carr, assistant secretary of state at the time, declared in a memo (!) about his issue with Jews on the boardwalk, among other places:

In a memorandum on Russian and Polish immigrants he wrote, “They are filthy, Un-American and often dangerous in their habits.” After a trip to Detroit, he described the city as being full of “dust, smoke, dirt, Jews.” He too complained of the Jewish presence in Atlantic City. He and his wife spent three days there one February, and for each of the days he made an entry in his diary that disparaged Jews. “In all our day’s journey along the Boardwalk we saw but few Gentiles,” he wrote on the first day. “Jews everywhere, and of the commonest kind.“

OMG! No way! as the kids say today. Again, in this day in age, it’s unbelievable that a politician would write this in a memo – a public document. The overt racism is difficult enough to comprehend, even if we admit that racism is more common today than we might like to admit (easy to say when you’re a white guy, of course). But can you imagine what would happen if someone working for Hilary Clinton, in the Obama administration, were to put such sentiments in a state department memorandum? The public outcry would be immediate and that person would be forced to resign just as quickly.

But as Larson illustrates In the Garden of Beasts as well as in interviews, such as the one with NPR’s Fresh Air, overt racism was indeed much more commonplace in Dodd’s time. Even Dodd himself, while not exhibiting the venomous attitude of Carr and Phillips, had his own prejudices when it came to Jews. While he is clearly mortified by the Nazi’s treatment of Jews, as a diplomat he does his best to try and sympathize in hopes of providing a moderating influence. In a discussion with Konstantin Freiherr von Neurath, the German foreign minister at the time Dodd was ambassador to Germany, Dodd discusses the Jewish “problem:”

Dodd pressed on, now venturing into even more charged territory: the Jewish “problem,” as Dodd and Neurath both termed it. Neurath asked Dodd whether the United States “did not have a Jewish problem” of its own. “You know, of course,” Dodd said, “that we have had difficulty now and then in the United States with Jews who had gotten too much of a hold on certain departments of intellectual and business life.” He added that some of his peers in Washington had told him confidentially that “they appreciated the difficulties of the Germans in this respect but that they did not for a moment agree with the method of solving the problem which so often ran into utter ruthlessness.”

But for daughter Martha, sympathy for the Nazi’s became more about rebellion than a matter of racism or support for German fascism.

On a personal level, however, Dodd found such [attacks on Jews] repugnant, utterly alien to what his experience as a student in Leipzig had led him to expect [of Germany]. During family meals he condemned the attacks, but if he hoped for a sympathetic expression of outrage from his daughter, he failed to get it. Martha remained inclined to think the best of the new Germany, partly, as she conceded later, out of the simple perverseness of a daughter trying to define herself. “I was trying to find excuses for their excesses, and my father would look at me a bit stonily if tolerantly, and both in private and in public gently label me a young Nazi,” she wrote. “That put me on the defensive for some time and I became temporarily an ardent defender of everything going on.”

After a year in Germany, however, even Martha comes to realize what is happening in. This is in spite of, or perhaps in some respects, because of, the fact that Martha socializes with high-ranking members of the Nazi regime and the Gestapo. At one point Ernst Hanfstaengl, head of the Nazi’s foreign press bureau in Berlin and a personal associate of Hitler,

even tries to fix up Martha with no less than the Führer himself. In person, the cult of personality that surrounds Hitler becomes more understandable; he comes across as anything but a clown to Martha.

She walked to Hitler’s table and stood there a moment as Hitler rose to greet her. He took her hand and kissed it and spoke a few quiet words in German. She got a close look at him now: “a weak, soft face, with pouches under the eyes, full lips and very little bony facial structure.” At this vantage, she wrote, the mustache “didn’t seem as ridiculous as it appeared in pictures – in fact, I scarcely noticed it.” What she did notice were his eyes. She had heard elsewhere that there was something piercing and intense about his gaze, and now, immediately, she understood. “Hitler’s eyes,” she wrote, “were startling and unforgettable – they seemed pale blue in color, were intense, unwavering, hypnotic.”

While Dodd’s book doesn’t directly address the larger questions that may plague us about World War II, the insights offered by the first-hand experiences of Dodd and his daughter are undoubtedly invaluable, not to mention fascinating.

But What Happens in the End?

If there is anything that In the Garden of Beasts might be criticized for, it might be that Larson seemingly spends an inordinate amount of time on the first year of Dodd’s tenure in Berlin, and little on the three that come after. Indeed, for the casual reader the details of Dodd and Martha’s lives at times might become a bit much. But then, after the Night of the Long Knives, there really isn’t much left to tell. By the summer of 1934, with the bloody purge and the death of Hindenburg, what comes next is the inevitable stuff of history. The only things that might stand in the way of Hitler and the Nazis are powers outside of Germany’s borders, and we already know at this point that the warnings emanating from Berlin have fallen largely on deaf ears. Indeed, after Hitler’s purge swept across Germany in June of that year, Dodd considered stepping down.

For Dodd, diplomat by accident, not demeanor, the whole thing was utterly appalling. He was a scholar and Jeffersonian democrat, a farmer who loved history and the old Germany in which he had studied as a young man. Now there was official murder on a terrifying scale. Dodd’s friends and acquaintances, people who had been to his house for dinner and tea, had been shot dead. Nothing in Dodd’s past had prepared him for this. It brought to the fore with more acuity than ever his doubts about whether he could achieve anything as ambassador. If he could not, what then was the point of remaining in Berlin, when his great love, his Old South, languished on his desk?

His Old South was a definitive written history of the southern United States; prior to becoming ambassador, that was Dodd’s primary goal for the remaining years of his life, to complete this grand, scholarly historical work. Ultimately he remained in Germany at his diplomatic post until the end of 1937, having been forced to resign – his enemies, the good old boys of the State Department, finally got their way in the end, as did Hitler and the Nazis, in the short term.

So were Dodd’s efforts in vain? This effort took a huge toll on both him and his wife’s health; she died in May of 1938; he died less than two years later. He never finished his beloved Old South. I suppose I should leave the answer to that to the reader to discover. While there are perhaps no spoilers in terms of the larger story that serves as a backdrop to In the Garden of Beasts – we know who won World War II, after all, and what happened to Hitler (more or less). But there is still much to learn and much that history can tell us, as Larson’s book illustrates.

Those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it, and that’s perhaps as important lesson today as it ever was, given not only the geopolitical climate at large today, but the political climate here in the United States. Here in this post 9/11 America, people who tend to get upset about things like the Patriot Act, Guantanamo, torture and the holding of suspects indefinitely without due process of law, are often countered by the argument “it can’t happen here.” The Germans — and the world at large — said the same thing in the 1930s.